Student Learning Assessment

Introduction:

As part of my student teaching journey, I was required to pick a standard that the class could benefit from in specialized instruction. The standard i chose was, “Elaboration of Evidence”. Looking at our writing unit scores from the beginning of the semester, I noticed that- overall as a class- we were lacking in our elaboration of evidence to prove our point in a character claim. The students had their evidence, but failed to tie the evidence to their reason, and their reason to the claim. These scores will serve as the pre-assessment for the SLA project. I decided that I would teach them this process in our Literary Essay unit. I would teach the standard of elaboration of evidence by pulling these students for one-on-one conferences, mini-groups (if applicable), and ensure my overall class instruction was clear and intriguing. The measurement of growth in this skill will be determined with a post assessment. The post assessment is a writing rubric implemented by the district.

Section 1. Goals and Standards

My goal is to have the students be able to elaborate their evidence and have the students will be able to tie the evidence to the reasoning. This is the standard of 6.W1: Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence. I will be focusing on the subheading of 6.W 1b : Support claim(s) with clear reasons and relevant evidence, using credible sources and demonstrating an understanding of the topic or text. This standard is one that is taught multiple times over the year, and it supports the 7th grade ELA expectations as well as district and state standards for Common Assessments and standardized testing.

Section II. Assessment Information Gathered:

The pre-assessment that I used was the grade for Elaboration of Evidence from our January writing assignment on Character Trait Essays. My mentor, Dana Abbasse, gave me this rubric, as it is a part of the Lake Orion District Power Standards. Lake Orion practices Standard Based Grading, which means the students may earn a 0-4 (.5 increments as seen fit). The breakdowns are as follows:

Proficient 4: Student consistently provided high-quality evidence of the standard being assessed.

Proficient 3.5: Student consistently provided quality evidence of the standard being assessed.

Progressing 3: Student provided general evidence of the standard being assessed.

Basic 2: Student provided inconsistent evidence of the standard being assessed.

Area of Concern: 1 Student provided little to no evidence of the standard being assessed.

No Evidence: 0 Student did not provide evidence of the standard being assessed.

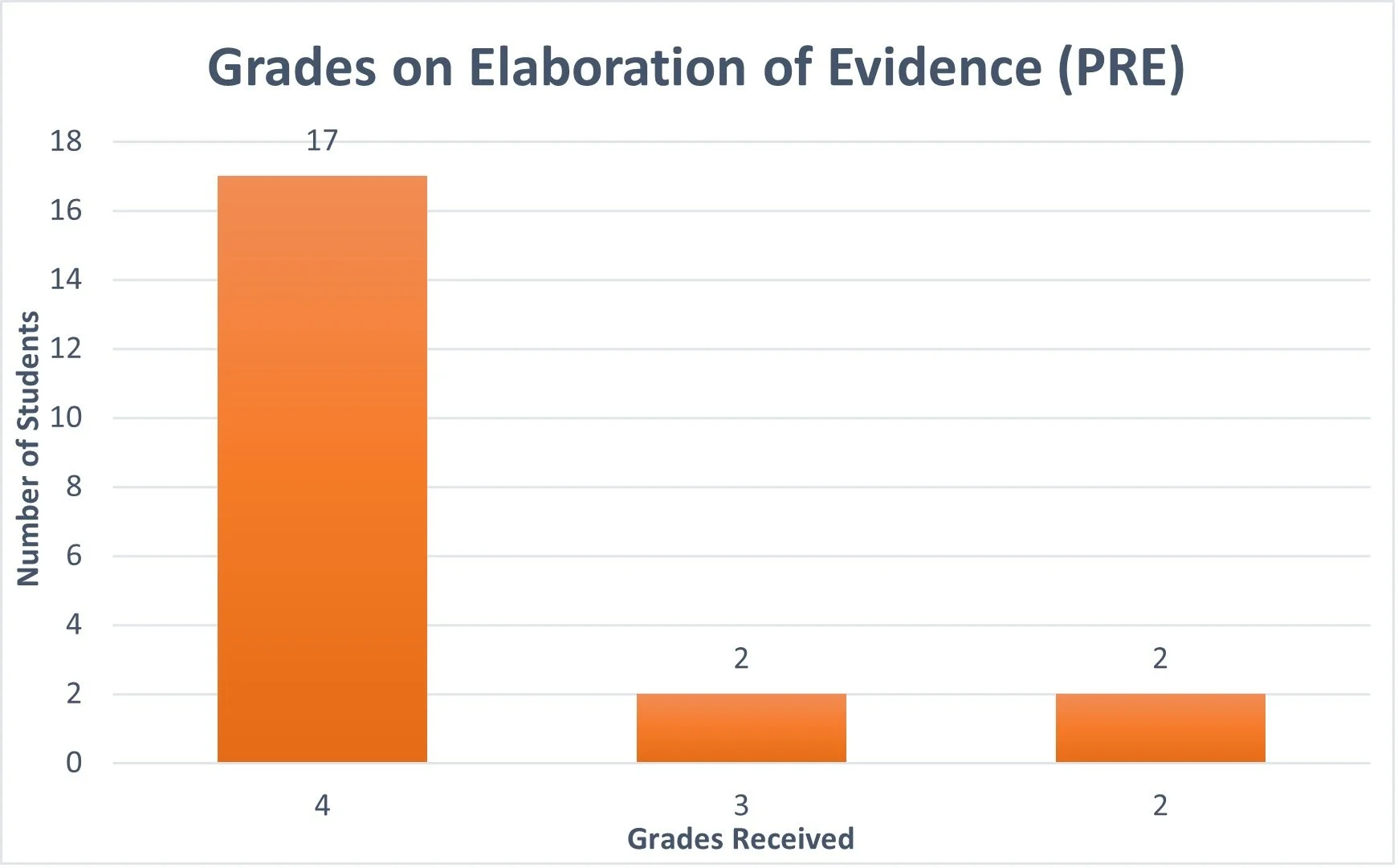

At my placement, I was available to help the students during writers’ workshop, so I had a hand in grading the essays. While grading, I noticed that students were overall struggling with the concept of elaboration of evidence. Even those in the top of the class were barely grasping the concept. The essay was a class assignment, so all of the 6th Grade ELA students developed a character trait essay, however, I chose one varied hour to be my control group. Chart A. is the bar graph of the Pre-Test Assessment grades for Elaboration of Evidence.

Figure A. Chart of Pre-Test Scores, January 2023

As the data shows, the class has a variety of grades and understanding of the subject area. My goal is to increase their understanding and to elaborate their evidence in future essays. Of the 21 students in the class, 17 earned a 4 (80% of the class) in elaboration of evidence. Of the 21 students, 2 students earned a 3 (10.5% of the class), as well as 10.5% of the class earning a 2. I will focus on two students (in the assignment only, not in the instruction) who received a 3 or under in Elaboration of Evidence for this upcoming unit. This data shows the need for more instruction area for Student One and Student Two. Note: Two of the students who earned a 2, never turned in their assignment (as of the final day of the SLA), and missed 27 days of instruction.

Section III. Analysis of Student Thinking:

According to Figure A . Chart of Pre-Test Scores, the class has a variety of grades and understanding of the subject area. My goal is to increase their understanding and to elaborate their evidence in future essays. Even the students who received 4’s, did not truly grasp the full understanding of fully fleshing out our evidence and how the evidence ties to the reasoning. There is one student in the class who actually would earn a 4 in a high school setting. They fully understand the assignments and can explain the evidence in a clear way. The other 14 students understood the concept, but did not use transitional phrases to guide the reader through their phrases. Or, they just had all three pieces of evidence, and did not tie them back to their claim or reason. For the first essay, this was still considered a 4, but for our literary essay, they will need to up the ante. The four students who earned a 3 are close to grasping the concept, and I will put them into focus groups during writing. These are the students I aim to show growth and an increased understanding of the skill of elaborating evidence. The Pre-Assessment grades were submitted into PowerSchool and were part of the First Semester GPA. The individual standard of Elaboration of Evidence alone will not determine the invitation to Academic Literacy. It is possible for a student to earn a 4 overall on their essay, and receive a 3 or 3.5 The Post-Assessment grades on elaboration of evidence will be entered into Power School as Semester Two GPA. I had a lengthy discussion with Dana Abbasse regarding the standard of Elaboration of Evidence. She and I decided that the students would benefit from a finite focus of elaboration. The main feedback of what the students were lacking in their writing will be incorporated into my lessons and during my conferring with Student One and Student Two. I will utilize formative assessments and exit tickets daily to help shape and design my lessons and formulate my instruction pattern.

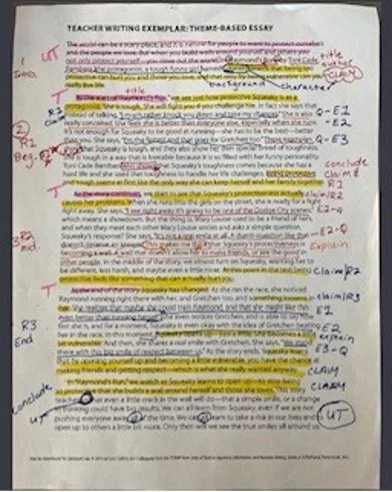

Figure B. Annotated Essay Mentor Text

Section IV. Future Instruction:

I began the Literary Essay Unit with notebook entries of character analysis, themes, motifs, and evidence from a short story. Then, I had the students fill out an exit slip about the character claim and reasoning (formative assessment). That night, I corrected and gave feedback about the slips to the students so that they could begin their outline in the next class period. The next day, I began the lesson with a big review of what an essay is, “We remember the structure of our character trait essay, yes? Can anyone tell me what comes first? What is the name of that FIRST paragraph?” The students then turn and talked to their partner (using sociolinguistic practices) and had a group refresh on the order of an essay. Then, I led the class in annotating a mentor text of a Literary Essay with our mentor text, “Raymond’s Run” on the Smart Board through the DocCam. I went over the first two paragraphs, and then had students break off into groups to annotate the rest. For the first paragraph, I highlighted and discussed the following: the Universal Truth, the title, the author, the main character’s name, the slight background in the story (exposition), and then the character claim. For the second paragraph, I identified and highlighted the title of the story, the Reason One Claim, the quotes from the story utilized, and the three pieces of evidence. Then, I highlighted the concluding sentence. (See Figure B.) While this was happening, I walked around and checked in on student’s thinking. Our focus was identifying our claim, three reasons, and Evidence (1, 2, 3) for each reason. We did not focus on the conclusion, as that will be addressed later in instruction. After annotating, we found our 9 pieces of evidence and three quotes in our short stories. I encouraged the students to “set themselves up for success” by really focusing on labeling the full evidence such as R1 E3 for Reason 1, Evidence 3. I saw a lot of E3, E2, and E1 but no R labeling, so I stopped the class for a quick interjection. This seemed to work, because by the end of the hour, every student had their evidence clearly labeled and ready to be input into an outline format.

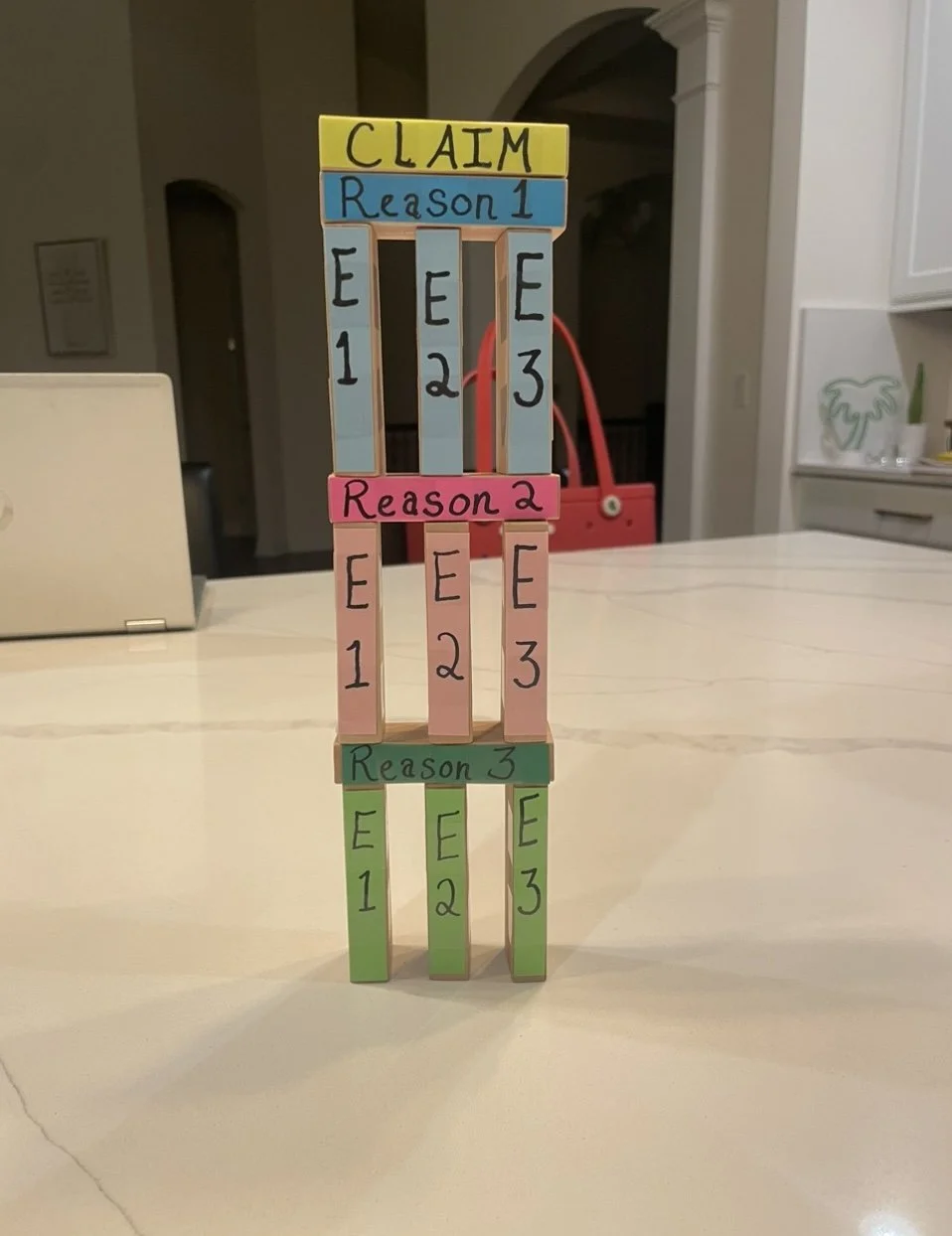

I know from previous research, that visual demonstrations are key to understanding concepts. So, I brainstormed a way that I could demonstrate what a strong essay is comprised of. I came up with the idea of a Jenga Tower. I pulled colored paper and labeled each block with a different part of an essay, (Claim, Reason 1: E1, E2, E3. R2 and 3Es, and Reason 3 with 3E’s). I visually showed what a strong supported essay looks like, then I asked the students what would happen to the tower if I pulled one piece of evidence out? The students responded in unison, “IT WOULD FALL!” (Excitement noticeably in their voices). We all cheered as I pulled Reason 2 Evidence 3 from the tower, scattering the blocks in every which way! “Is that a strong essay?” I implored. “NOOOOOO!” the class roared back. (See Figure C)

Then, I gave the students and checklist and modeled how I would explain my evidence to a partner. I made sure I gave my claim, my three reasons, and how they tie into my claim. Finally, I gave my nine different pieces of evidence, and explained how they supported my reasoning. This was our first introduction into the standard of Elaboration of Evidence. After I modeled this, I encouraged students to do as I did, and explain everything to a partner. I am a strong believer in using modeling to ensure the students understand what is expected of them. While they went through their outline, their partner checked off the list. While I was walking around, I heard, “I don’t think your tower is super strong right now. I think you are missing two pieces of evidence for R3. Let’s try and find some!” This was said from Student One to Student Two of my project. This demonstrated that the students understood the lesson, and then they were actively incorporating the lesson into their own writing of their outline. My model is beneficial to students, and I decided that I will place the model in the front of the room for the duration of the writing unit.

Figure C. Jenga Tower of Essays

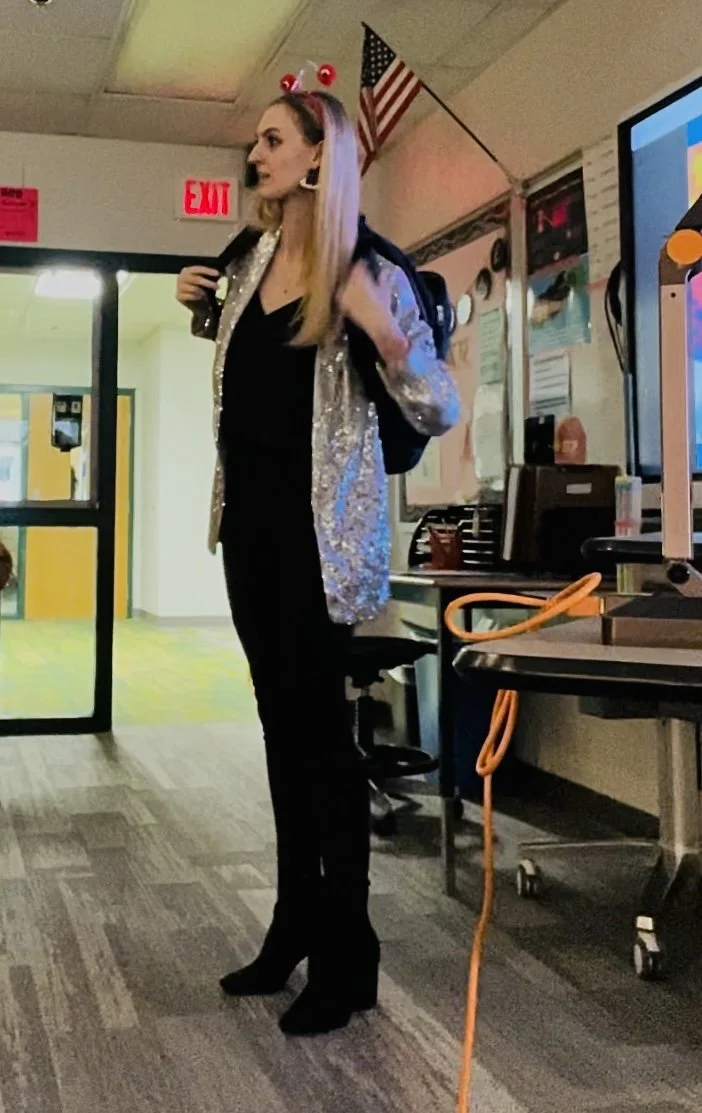

Meet Miss Gazorka

My big lesson on Elaboration of Evidence was a key part of my teaching. I knew I had to create an exciting hook to the lesson, so I decided to become an alien. Miss Gazorka from Planet Essay visited Miss Morton’s class on Thursday, February 23rd, 2023. (See Figure D) She had a very important question to ask the class.

“Greeting, earthlings. My name is Miss Gazorka. I am from the planet of Essay, many lightyears away. I have landed on this strange planet, and I want to ask you a very important question: What is that?” (points at backpack) “Please gather in your table groups and for the next three minutes, I want you to create a mini- presentation about what “that” foreign object is, why do you use it, how does it work? Then, you will present this 30 second pitch to me, Miss Gazorka!”

Miss Gazorka (me) then followed the directions as the students gave information about a backpack to her. She had to have the students explain what a zipper was, what arms are, and what you could place in a backpack. After the students gave their mini presentation to Miss Gazorka (and she understood how a backpack worked), she thanked the students for their help and left for Planet Essay. Then, I exited the classroom, took off my alien headband and came back into the classroom and said, “Give yourself a round of applause! I bet you are wondering why we did that goofy exercise? You all proved that you could explicitly describe what a backpack is to some being that has never heard of a backpack before! You were able to elaborate your evidence and explicitly describe to an alien how a backpack works. When we are writers, we must treat our readers like they are aliens-in that they know nothing about our story. We must be explicit in our elaboration of evidence.” (See Figure E) Then, I modeled how to do this in front of the class. I used the sociolinguistic property of “Turn and Talk” for this part of the lesson. The following is the exact wording I used during the lesson.

Figure D. Gazorka Learns What a Backpack Is

Figure E. Gazorka Teaching Point

“Today, I am going to teach you that strong writers not only have their nine pieces of evidence, they connect their evidence to their reasons, and they connect their reasons to their claim using sentence starters and transitions. This helps to elaborate our evidence and further explain our point. When you write an essay, you need to treat your reader like an alien- in the idea that they have NO background knowledge prior to reading your essay. You must clearly state your reasoning, and then you must connect your evidence to the reasoning. Let’s take a look at our outline. Can I just copy exactly what is on my outline down into my essay and call it good? 9Then I read outline R1. E1. E2, E3.) Thumbs up if this is a good essay. Thumbs down if not. TT why or why not!! Right! We must elaborate quite a bit more to get our point across! Remember how we had that green checklist with our partner, and we had to explain how our reasons tied into our claim and then how our evidence supported (or held up) our reasons? What happens if our Jenga blocks were made from a soft collapsible material? What would happen? We need to build up our evidence with explanations to give our structure support! Today, we will begin writing our first reason (or beginning) paragraph. It is not enough to have our first reason and three pieces of evidence and a quote. We MUST connect these ideas together to form a coherent paragraph for our reader, by elaborating our evidence. We cannot simply say, “Squeaky is defensive to everyone she meets. I much rather knock you down and take my chances.” (pg.2) So, Squeaky has had a hard life. Is this strong? Thumbs up or thumbs down! (Formative Assessment) I agree, let’s add some sentence starters to make this more cohesive, shall we?

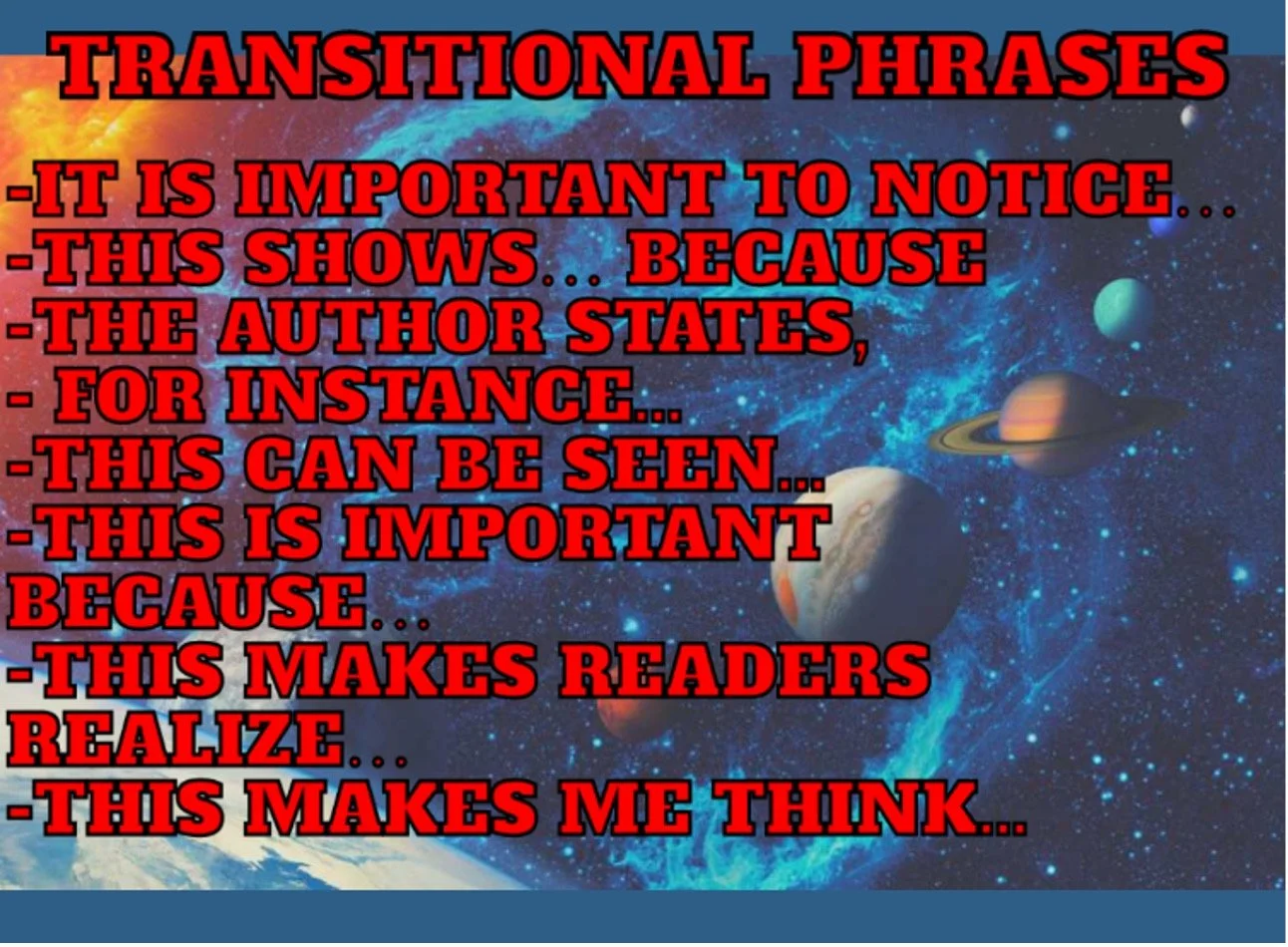

Let’s take a quick peek and write down these sentence starters for safe keeping! (Display paper with great sentence starters).

- This shows.. because

- It is important to notice…

- This is significant because…

- The author states

- For instance

- This can be seen

- This is important because…

- This makes readers realize…

- This makes me think..

These internal transitions and sentence starters can really help us writers guide the reader through our reasoning and evidence and help us elaborate our evidence as well! Let’s try it with our sentences up here!” Then I displayed the following on the board , asking the students to raise their hand when they saw a transitional phrase:

In the beginning of “ Raymond’s Run”, Squeaky is defensive to everyone she meets. The author states, ’I much rather knock you down and take my chances.’ (pg.2) This is significant because Squeaky has adapted her tough attitude to survive. This makes me think that Squeaky had a hard life, and she uses her toughness as a way to handle her life challenges. Do we all see how by adding a few sentence starters and explaining our evidence like we were talking to an alien that we have elevated our essay to the NEXT level?

Figure F. Transitional Phrases for Alien Elaboration Lesson

After this workshop time, I had the students write their Reason 2 paragraph. During this time, I conferred with the students about their writing. We already had all the student’s outlines approved, so the structure of their basis of writing was strong. It was all a matter of having the student’s piece together their reasoning with their elaboration. What I found to be successful, was that I brought around a lime-green sticky note with a pen to every student. During my compliment conference with a student, I would jot down the main points of what I had had given for advice. I would place the sticky note on the far bottom right corner of the student’s laptop. This gave me the visual aide to help the student remember all the points we discussed during our conferring time, and that next time I saw that student, I would check their writing against their sticky note. This proved to be a time saver and beneficial to the student and to me. One of the sticky notes I wrote to one of my focus students (Student One) was the following: “Title in “ “ and Capitalized, “Papa’s Parrot” . Make sure you have Page #’s after quotes. Miss Gazorka should not be confused!” The student incorporated all these suggestions into their writing. I found the sticky-note method to be successful.

The following is an excerpt from Student One ‘s work in the pre-test. “The only other person Squeaky likes is her dad because he used to be a runner and can relate a lot to him and likes him because He’s nice. But Squeak’s mom on the other hand Squeaky does not like her mom because she Is not nice, and she doesn’t want Squeaky to do running.”

SPICE UP YOUR WRITING

Figure G. Teaching Point for “Spice Up Your Writing”

The next lesson that was relevant to the Standard of Elaboration of Evidence was “Spice Up Your Writing!” In this lesson, I created Chili Peppers out of construction paper, and wrote different external transitions, internal transitions, and appositive forms on them. The teaching point of the lesson was to “spice up your writing with transitions and appositives”. (See Figure G) Then, I had the students workshop using the different peppers in a group setting, using paper strips with sentences on them. (See Figure H) After the students found the order they would like the strips to be placed in, they added transitions and appositives in to make their writing spicier. (See Figure I) After this was complete, we went around to every group in the class and decided if the writing was spicy or not, and we also identified the appositives in the sentence as well. From there, I encouraged the students to write their own transitions in using the peppers on the table. From here, the students worked on their Reason Three paragraph. During the work time, I conferred with students I had not previously met with the day before.

Figure H. The Chili Peppers Manipulatives with Transitions

Figure I. Directions for Spicier Writing

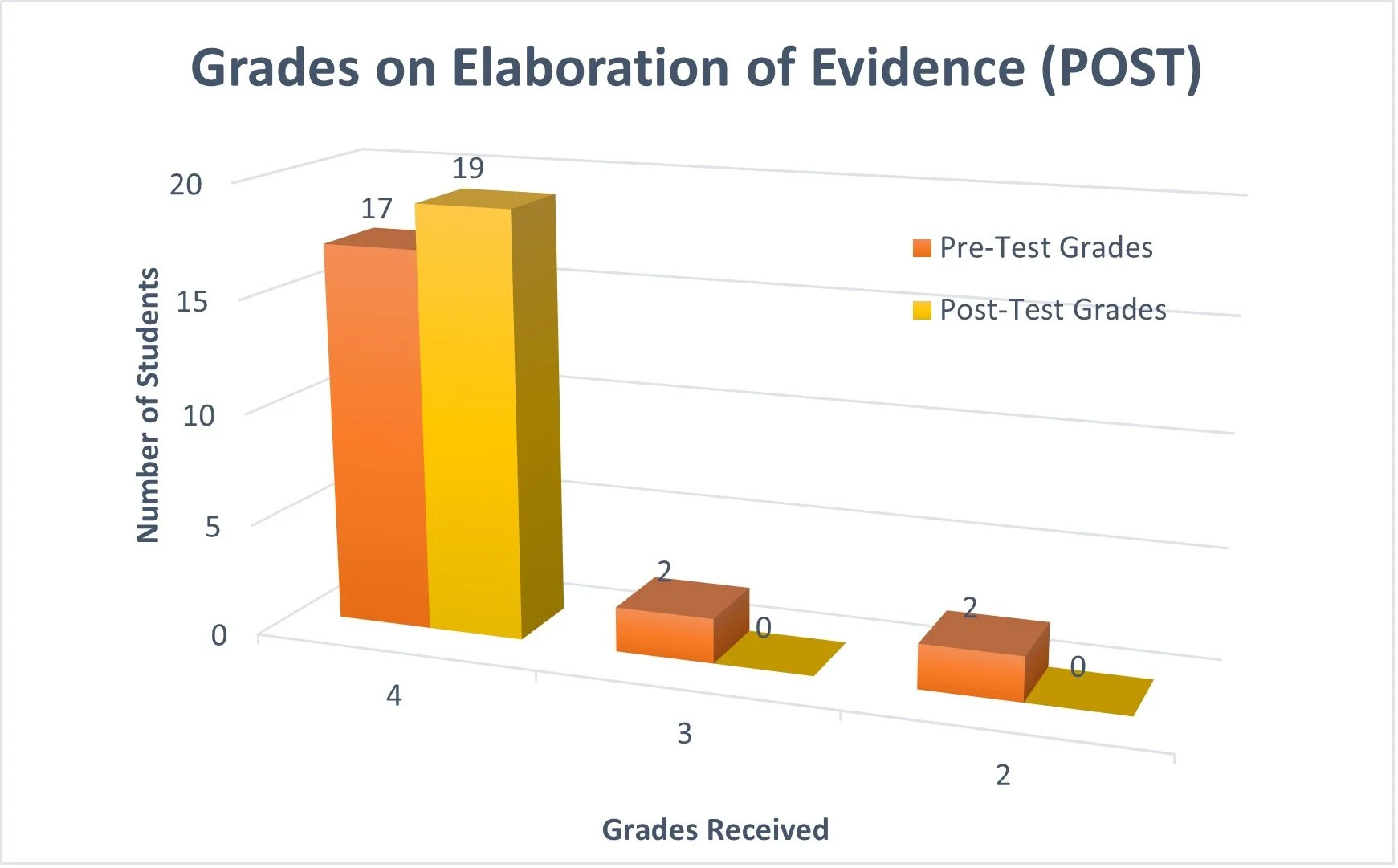

Figure J. Post-Assessment Graph with the Pre-Assessment Graph Scores, March 2023

SECTION V: RESULTS

Looking at Figure J, the grades in the class for Elaboration of Evidence increased exponentially. Even Dana Abbasse stated that, “I have never had such a success in the essays. These are the best batch of papers I have ever received.” I focused on Student One and Student Two for this SLA project. Student One had a 3 on elaboration last unit, and I felt that I could move them up to a 3.5, or even a 4. The student needed quite a bit of work on finding our evidence before we could focus on elaboration. Once the student had a solid 9 pieces of evidence, we were making progress. After my alien lesson, the student began explaining his evidence clearly and explicitly. The big moment that altered his writing for good was the introduction of transitional phrases. This student is easily a 4 in writing argumentatively now, increasing their score 25% from the Pre-Test. Below is an excerpt demonstrating his skill of elaboration of evidence. The student utilized the transition lesson, and overall, he had spicier writing. His elaboration demonstrated not only an understanding of the text, but also a deeper understanding of the surface level. Below is an excerpt of Student One’s Elaboration from the Pre-Test. The following is an excerpt from Student One ‘s work in the pre-test. “The only other person Squeaky likes is her dad because he used to be a runner and can relate a lot to him and likes him because He’s nice. But Squeak’s mom on the other hand Squeaky does not like her mom because she Is not nice, and she doesn’t want Squeaky to do running.”

Compare this with his elaboration of “After his dad had a heart attack Harry must take care of the candy shop and the parrot. He gets mad at the parrot because it asks, “Where's Harry?” (pg. 4) when Harry was right in front of the parrot. This is important because Harry wasn’t at the candy shop when he got older, but his dad had a heart attack, and he regrets he wasn’t with him at the candy shop for more time. He knew that his Papa missed him, because parrots repeat what they hear.”

Student Two had a large success as well, escalating for a 3 to a 4 in elaboration (25% as well). The bulk of his success was in the use of transitional phrases. This student used all of the different transitions that I demonstrated in class and was actively holding up and deciding which pepper to use for their essay. This further proves that manipulatives reach students who may not have otherwise been reached before.

The other two students I had planned to focus on originally were not in school for the entirety of the unit. My mentor teacher recommended I remove them from my data because they were outliers with 0’s. They did none of the work online I sent them through Teams as well. They missed 22 days of instruction. Those students have been cleared medically to not complete the assignments they missed during that period. Of the grades that we had for the students in class, none of the students dropped below what they were at. Student One went from a 3 to a 4. Student Two went from a 3 to a 4. Overall, the class improved on the elaboration of evidence. This is important because this was their first Literary Essay (of many to come). It was imperative that I lay down a strong foundation for my students of knowing how to write a literary essay.

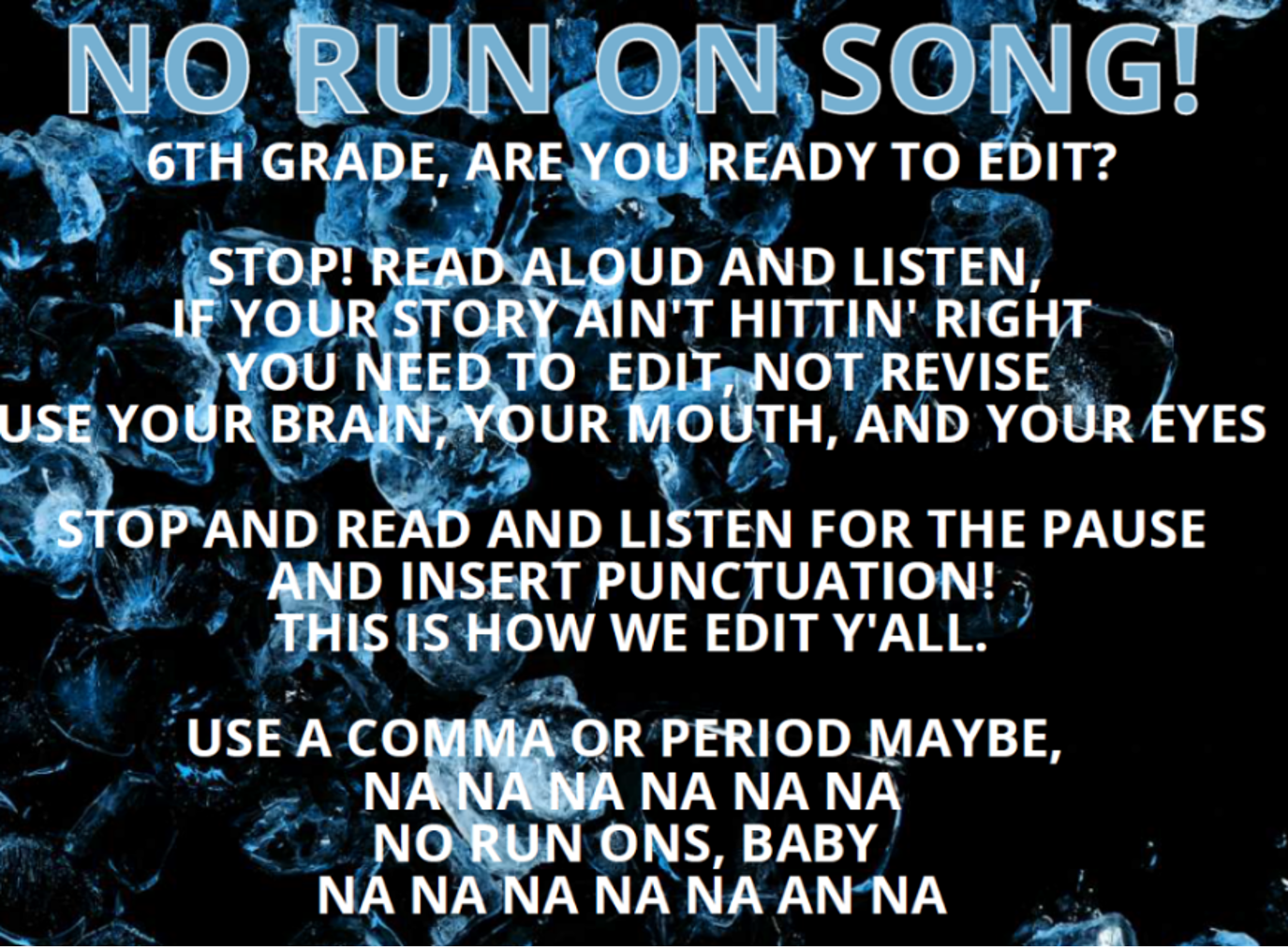

CONCLUSION

I think I did a successful job teaching this standard of Elaborating Evidence. I spent substantial time coming up with intriguing and interactive lessons for the students. I used manipulatives to visually demonstrate the importance of elaboration, and made chili peppers with external and internal transitions on it. This was used for my lesson, “Spice Up Your Writing!” which helped the students visualize the use of transitions and see how they can make their writing so much better than before. I used “Turn and Talk” (sociolinguistic properties), group work, and one on one instruction to further the student’s understanding of the lessons I taught regarding elaboration. I also wrote a rap to the song, “Ice, Ice, Baby” and performed it karaoke style for the class. (See Figure K) This song was to help the students fix their run-on sentences, which helps their elaboration be clearer. Click to see and hear "No Run-Ons, Baby!"

Figure K. “No Run-ons, Baby” Rap Lyrics

I completed fun, themed, power points via Vista-Create and included what the student’s referred to as, “Dad Jokes”. In my opinion, if the students are groaning, they are listening and actively participating. After a while, the students began competitions to come up with even more groan worthy jokes about the lesson. To celebrate the unit, I took my conclusion lesson (“The Scoop on Conclusions” Figure L), and I brought in sundae ice cream cups for the students. While they were eating their ice cream, they read their essay out loud to another partner. This was our celebration of ending our writing unit. The students really enjoyed this part.

Figure L. Here’s the Scoop Lesson Teaching Point

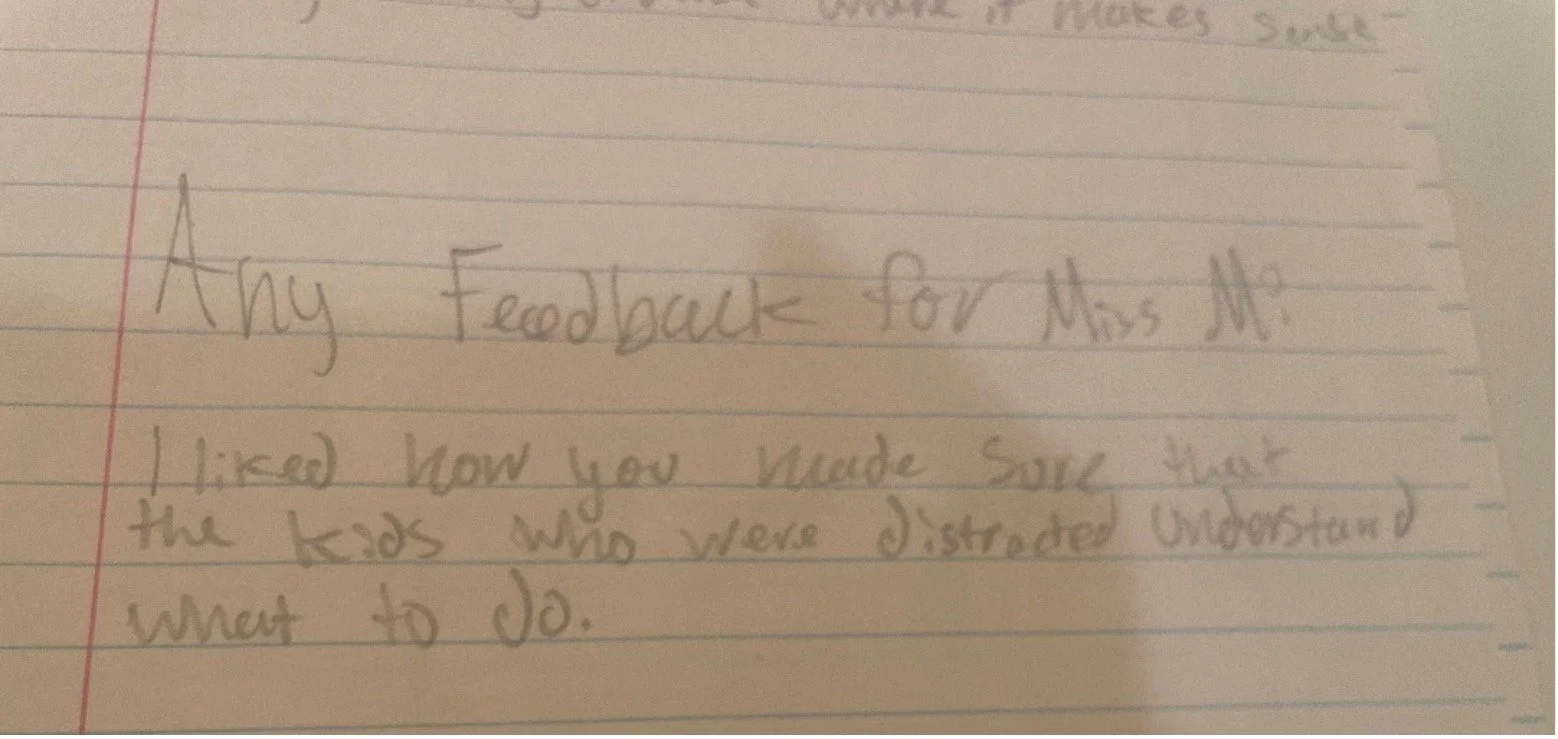

I also had the students fill out an exit ticket responding to the following prompts: 1. I am proud of… 2. I want to work on…and 3. I have the following feedback for Miss M… From the answers of what the students were proud of, I made a word art collage incorporating what they had answered. I chose to make this in the shape of a light bulb, and I displayed this on the whiteboard for all the hours the next day. See Figure M.

Figure M. Proud Collage

Some of my favorite feedback I received was, “Miss Morton, can we do Text Structures with Shrek?” I ended up finding a Shrek song to do for my Figurative-Language Fun Friday the next week. Another one of my favorite feedback items was, “You acted like an alien, and now I think of Miss Gazorka when I write!” This feedback is from Student Two. The best one was, “I liked how you made sure that the kids who were distracted understand what to do.” This proves that during the unit, I reach all my students and other students notice that everyone is on the same page before I move on in instruction. This is the hallmark of being a good educator. Through this project, my idea of the importance and magnitude of using assessments has been validated and reinforced.

Figure N. Feedback Slip